Who Was The First Magician In Canada?

Colonial Conjurers: The Pioneering Magicians of British North America

"Who was the first magician in Canada?"

As a professional American magician navigating the path toward Canadian citizenship, my curiosity sparked a simple question: "Who was the first magician to perform in Canada?" Much like the flow of goods and various commodities traversing the colonies, magicians traveling from England and Europe to America often performed on Canadian soil. Entertainers of diverse backgrounds ventured northward into these lands, seeking work opportunities.

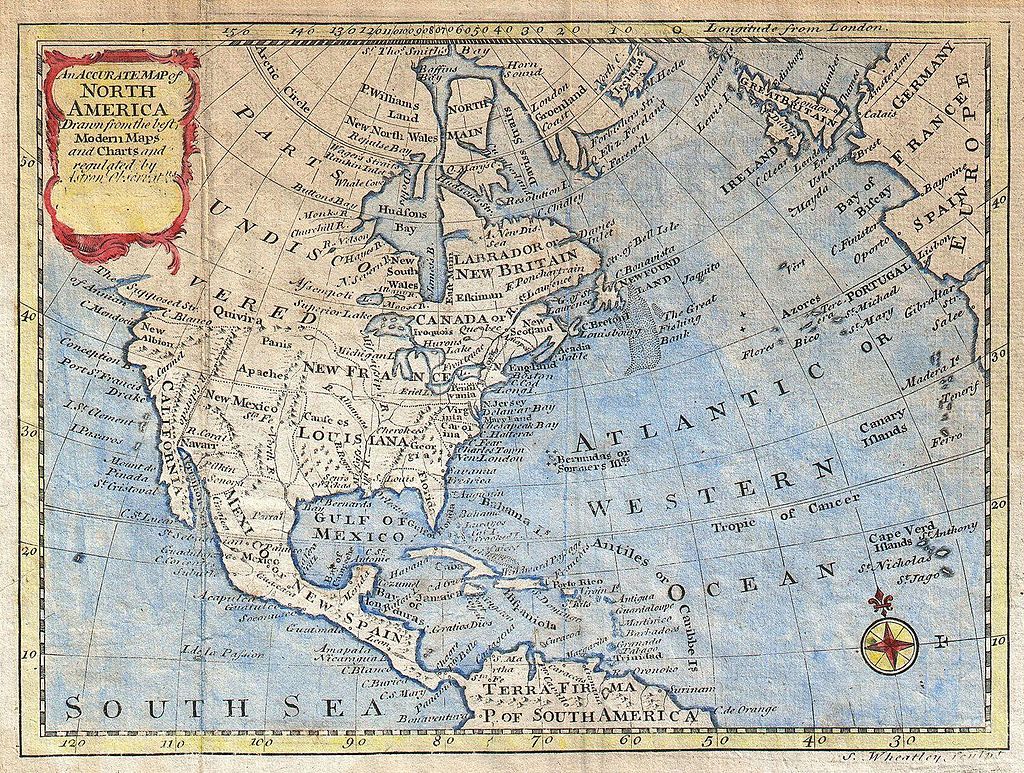

A typical course of travel would involve landing on the American shores in Philadelphia, New York, or Boston, then heading north of Maine, beyond New Brunswick, performing in Halifax, Nova Scotia, then descending the St. Lawrence River to captivate audiences in Quebec, Montreal, and more. “The largest cities were on the coast, and it was easier to travel by sea [and river] rather than over land, as there were no rail systems and the roadways that existed were often little better than ruts cut through the forest—ruts that would be rough when dry and quagmires when wet.” 1

It’s important to note that exploring this inquiry took me on an unexpected historical journey, revealing a crucial and overlooked detail. The magical practices of Indigenous shamans and medicine people, the original enchanters on Canadian soil, deserve credit and acknowledgment as the first magicians. A dedicated exploration of this topic in a future article is warranted. Yet, in this article's context, I emphasize the archetype of a Western-style conjuror, as initially envisioned.

Acknowledging that present-day Canada likely did not exist during this specific period, our focus adjusts to what was known as Upper and Lower Canada in the era of British North America.

Please allow me to introduce you to a handful of colonial conjurers without further ado.

Mr. Samuel Jameson Maginnis: The Trailblazer (1794)

“The first recorded White magician to perform in Canada was probably a man named Maginnis.” 2

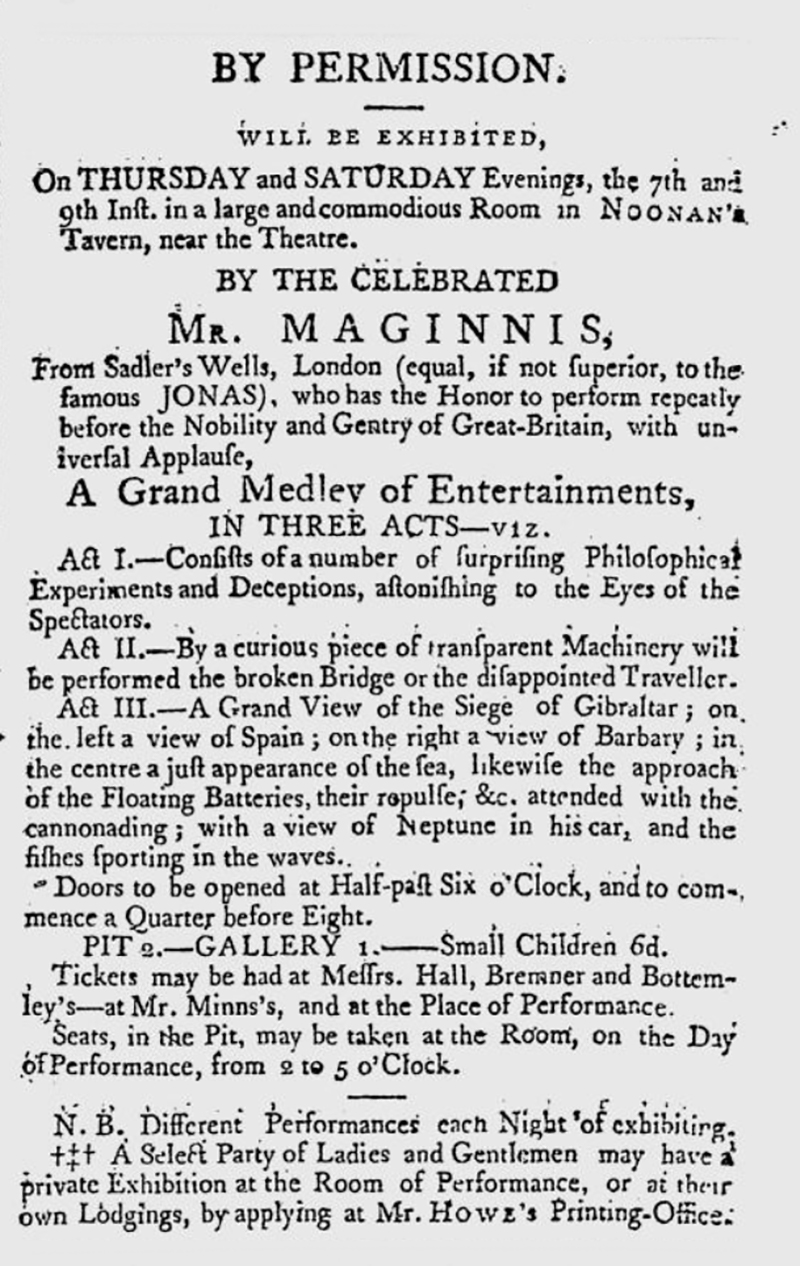

In August 1794, an advertisement for Maginnis, a skilled British magician and actor who honed his crafts through training at the renowned Sadler's Wells Theatre in London, appeared in Halifax’s Royal Gazette. Notably, Sadler’s Wells Theatre remains an iconic venue that continues to operate. Here, Maginnis “performed repeatedly before the nobility and gentry of Great Britain with universal applause.” 3 It was North America’s moment to witness the mesmerizing display of this magician's unique expertise.

On the 7th, 9th, 14th, and 16th of August as well as the 2nd, 4th, and 6th of September, 1794, at Halifax’s Timothy Noonan's Tavern, Mr. Maginnis captivated his audience with a spectacular array of performance art, presenting what he called a Grand Medley of Entertainments. Historical records indicate his three-act spectacle unfolded with illusions, sophisticated machinery, and a stunning panoramic portrayal of the Siege of Gibraltar. “His performances usually ran from one hour to one hour and a half and consisted almost entirely of sleight-of-hand such as the cups and balls, and tricks with simple equipment as described in Henry Dean's ‘The Whole Art of Legerdemain or Hocus Pocus in Perfection.’” 4

While it's challenging to definitively state whether these are the first recorded advertisements for performances of the first Western-style conjurer in British North America, they provide valuable glimpses into the promotional efforts of early magicians.

Documents also reveal about five months later, on March 31st, 1795, Mr. Maginnis graced Noonan's in Halifax again, offering performances at the tavern or in private lodgings. 5

After his 1795 appearance, Maginnis dropped off the radar, leaving his whereabouts shrouded in mystery until his unexpected reappearance in Portland, Maine, in May 1798 in a show advertised as Exhibition of Innocent Amusements. We again caught sight of Maginnis in Philadelphia in August 1803. 6 Then, we found him later in Washington, District of Columbia 7, the following winter.

The final reference to Maginnis by any of his contemporaries appears in William Frederick Pinchbeck's 1805 work Witchcraft: or the Art of Fortune-Telling Unveiled 8, which adds an intriguing element to his historical narrative. Following this, Maginnis slips into obscurity.

Samuel Jameson Maginnis's influence extended beyond the curtain, paving the way for a lineage of magicians who would follow in his footsteps, captivating audiences in British North America. While the debate persists on whether he was the absolute first, what remains undeniable is his role in initiating a tradition that attracted numerous magicians to perform in the region.

Monsignor Martin: The Tightrope Walker (1798)

Before Mons. Martin performed on British North American soil, he entertained audiences in America.

On August 25th, 1793, Mons. Martin took the stage on a summer evening in Boston, advertised as a Pantomime to dazzle the audience by “doing a trick with a hat.” 9 The moment marks one of the earliest instances of magic debuting in Boston, even if “Mons. Martin wasn't a member of the profession.” 10 He earned his livelihood as a performer and tightrope walker, captivating audiences for financial support.

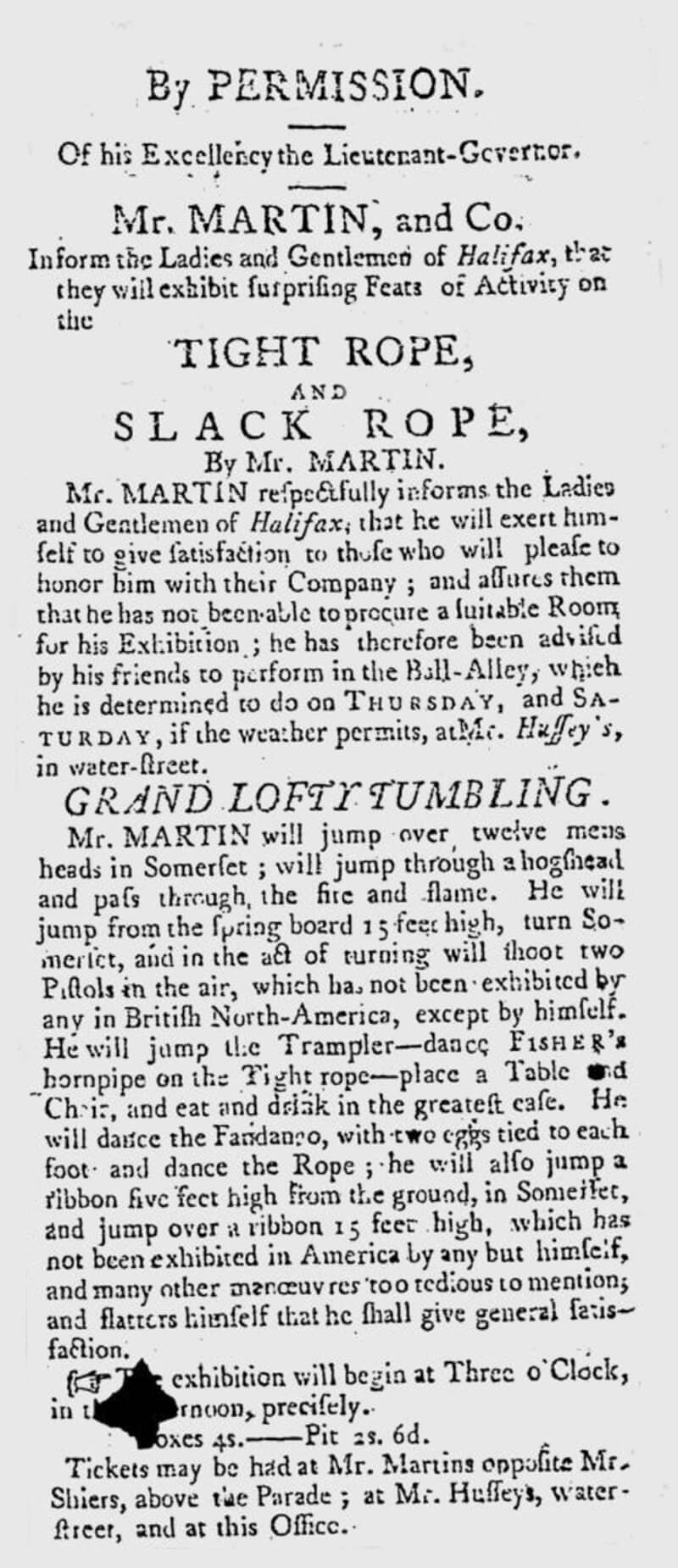

When Mons. Martin took the stage at Ball-Alley and Mr. Hussy's in Halifax in October 1798; he brought his magic repertoire that had likely expanded since his earlier performances in Boston. However, his British North American show's primary emphasis centered on the tightrope, grand lofty tumbling, and slackline walking. 11

Mons. Martin perhaps helped lay the foundation for cultural exchange, enriching the local Halifax arts scene and fostering a tradition of magical and theatrical expression that would endure for generations.

Gabriel Salenka: The Dog Handler (1799)

Gabriel Salenka made his mark in 1796, performing magic for audiences along the eastern seaboard of America. Renowned for “collaborating with a dog trained by himself who performed card tricks,” 12 their remarkable feats included telling time, executing impressive card tricks, and curating an otherworldly experience.

In the spring of 1799, “Salenka became the first magician to perform on New York’s Wall Street.” 13

Not long after, on August 10th and 13th, 1799, Salenka, his wife, and their sagacious dog visit Halifax to perform wonderful exploits and deceptions at Mrs. Sutherland's Long-Room. 14

On those two evenings, Canadians witnessed extraordinary magic by Salenka and his dog, highlighted by a fascinating magic bottle that dispensed liquor while simultaneously igniting a dazzling fireworks display. The curtains falling on both nights marked a momentous event in Halifax’s history and cemented Salenka's place as a pioneering colonial conjuror.

James Rannie: The Ventriloquist (1804)

James Rannie, born in Scotland around the late 1700s, and his younger brother John 15 played crucial roles in shaping the landscape of magic and ventriloquism in the new world. Their narrative unfolds in Scotland, where both brothers, seasoned performers, graced stages around the nation. A newspaper snippet proudly declares, “James Rannie a remarkable man,” 16 showcasing his ventriloquist and wire-dancing talents. Two weeks later, the younger brother, John, finds himself entangled in a legal web unrelated to performing. Arrested, charged, and convicted for an act known back then as "meal mobbing,” 17 John endured “a month of imprisonment and faced the additional consequence of a seven-year banishment from Scotland.” 18

Undaunted by adversity, the brothers navigate a new life trajectory. Seemingly fueled by the desire to continue performing, John and James embark on a daring adventure that carries them across the Atlantic to the United States via England. On a noteworthy tangent, some academics believe that “John Rannie was said to be the teacher of Richard Potter.” 19 As fate would have it, Potter would later emerge as the first African-American celebrity magician and would go on to perform in British North America.

James Rannie debuted on American soil at Lovett's Hotel on Broadway in New York City in December 1801 20. Performing north along the eastern seaboard, he eventually reached Montreal, recognized as part of Lower Canada, most likely utilizing the St. Lawrence River as a natural route.

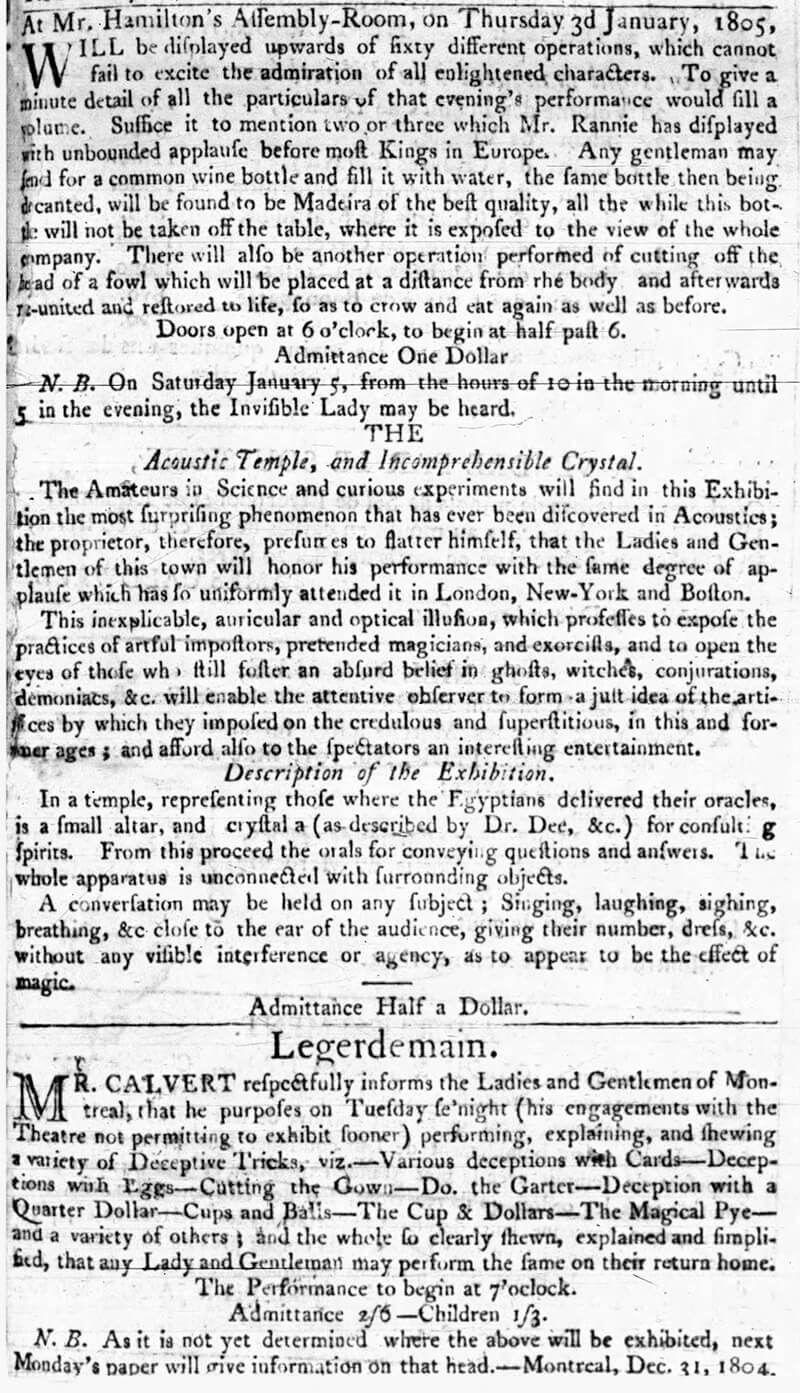

While we find a newspaper clipping about Rannie's ventriloquism show almost a month earlier 21, this particular clipping from a Montreal newspaper advertises his upcoming magic show on January 3rd, 1805, at Mr. Hamilton's Assembly-room, extolling how he would “perform upwards of sixty different operations, which cannot fail to excite the admiration of all enlightened characters.” 22

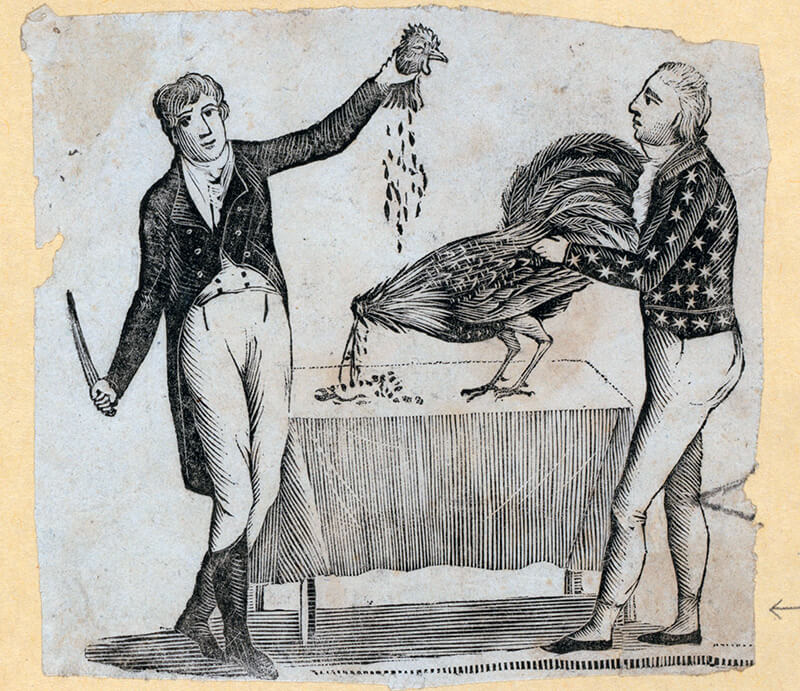

James Rannie’s magic performance transformed a regular wine bottle filled with water into the finest Madeira wine, all while the bottle remained on the table, visible to the entire audience. Another magical feat involved the apparent beheading of a fowl, with its head separated from the body. Then, magically rejoining the head with the body, the bird is restored to life, showcasing its ability to crow and eat normally (see woodcut above). Experiencing such incredible magic must have been breathtaking for anyone fortunate to see it.

At the bottom of Rannie's Montreal promotion, a remarkable "legerdemain" 23 advertisement catches the eye.

Mr. Calvert: The Magical Synchronicity (1805)

The first week of 1805 at Mr. Hamilton's Assembly-hall witnessed a fortuitous synchronicity in magical performances, first with James Rannie, then as Mr. Calvert added his magical flair to the Montreal landscape.

Mr. Calvert's performances showcased various magical feats, though details about his life remained elusive. He entertained his audience with feats involving cards, eggs, coins, cups, and balls. Though it all seemed short-lived. A few weeks after opening, he ran an ad in the Montreal Gazette complaining about closing his show “due to a breach of promise and contract by Mr. Hamilton's Assembly-hall manager.” 24

Regrettably, Mr. Calvert’s presence fades into silence after his Montreal appearance, and history offers no further trace of his endeavors.

Have We Found The First Magician In Canada?

So, was Samuel Jameson Maginnis the pioneer of Western-style magic in British North America? At present, he stands as the one we can trace through the corridors of history. However, as the pages of time often reveal, many magicians likely preceded him, their stories now veiled in the mists of bygone eras. Until that magical resurgence, we linger in anticipation, yearning for the revival of these forgotten maestros to once again illuminate the stage of our knowledge.

As I navigate the path to Canadian citizenship, I'm not just watching from the sidelines; I'm actively participating, adding my story to the larger tale of Canada’s magic. My citizenship is more than paperwork; it's diving into a shared heritage of stories, traditions, and the unbeatable spirit of those who paved the way. Let the legacy of these colonial conjuring pioneers serve as a reminder of the enduring power of magic to captivate and inspire, transcending borders and bridging the gaps of time.

NOTE: As of June 2nd, 2023, Lee Asher officially attained Canadian citizenship and now resides joyfully in Toronto alongside his wife, Christina, their Boxer puppy, Norman, and a massive playing card/magic collection.

Footnotes

- Pecor, Charles J. "The Ten Year Tour of John Rannie." David Meyer Magic Books, 1988, p.8.

- Booth, John. Creative World of Conjuring (Ridgeway Press, 1990), p. 153. "The Evolution of Magic In Canada."

- "By Permission." The Royal Gazette, Halifax, 5 Aug. 1794, p. 3.

- Mulholland, John. "Boston's Early Magicians," The Sphinx, vol. 41, no. 11, January 10, 1943, p. 240.

- "Mr. Maginnis." The Royal Gazette, Halifax, 31 Mar. 1795, p. 3.

- "Dancing Horse." Aurora General Advertiser, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 4 Aug. 1803, p. 3.

- "By Authority." The National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser, Washington, District of Columbia, 16 Nov. 1804, p. 3.

- Pinchbeck, William Frederick. Witchcraft: or the Art of Fortune-Telling Unveiled, Boston, 1805, p. 38.

- Boston Columbian Centinel, 25 Aug. 1793.

- Moulton, H.J. Houdini's History of Magic in Boston 1792-1915, Meyerbooks, 1983, p. 1.

- "By Permission." The Royal Gazette, Halifax, 30 Oct. 1798, p. 3.

- Braun, John, editor. "First Magicians In New York" by Melbourne Christopher. Linking Ring (International Brotherhood of Magicians), vol. 23, no. 5, July 1943, p. 24.

- New York Daily Advertiser, 16 Mar. 1799.

- "Exhibition." The Royal Gazette, Halifax, 13 Aug. 1799, p. 3.

- Hodgson, John A. "Richard Potter America's First Black Celebrity." University of Virginia Press, 2018, p. 54.

- Aberdeen Journal, and General Advertiser for the North of Scotland. Aberdeen Journal, Aberdeen, Scotland, 12 May 1800, p.4.

- “meal mob, a riotous crowd, demonstrating against shortage of oatmeal caused by holding supplies back to create big prices, freq. esp. in N.Scot. at the time of the Napoleonic wars and throughout the first half of the 19th c.; meal-mober, one who incites such a riot; meal-mobbing, the inciting of these riots." Dictionary of the Scots Language.

- Aberdeen Journal, and General Advertiser for the North of Scotland. Aberdeen, Aberdeen, Scotland. Mon, May 12, 1800, p. 3.

- Jay, Ricky. Many Mysteries Unraveled: Conjuring Literature in America 1786-1874 (1990), published by American Antiquarian Society, p. 5.

- "Ventriloquism" Montreal Gazette, Quebec, Canada. Mon, Dec 10, 1804, p 4.

- Odell, George Clinton Densmore Annals of the New York Stage, vol. 2, Columbia University Press, 1927-1949, p. 143.

- "Theatre." Montreal Gazette, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, Dec 31, 1804, p. 3.

- "Legerdemain." Montreal Gazette, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, Dec 31, 1804, p. 3.

- Montreal Gazette. Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Mon, Jan 21, 1805, p. 3.